Lessons from the Oracle

Key Takeaways

Warren Buffett emphasizes the importance of investing in equities to build long-term wealth, even in the face of inflation.

Buffett's investment philosophy has evolved to focus on high-quality companies with good prices.

Buffett advocates for reinvesting dividends to benefit from the power of compounding returns over time.

Many consider Warren Buffett to be the most famous value investor the world has ever known. This can be debated, but with an investment career that spans nearly seven decades, he has undeniably learned a thing or two about markets. How else would you get a nickname like the Oracle of Omaha?

An enduring and often revered feature of Buffett’s approach as CEO and chairman of Berkshire Hathaway is the openness with which he offers details of the decisions he makes on behalf of his company’s shareholders and his propensity to share hard-earned investment wisdom. He packs such insights into a lengthy letter in the Berkshire annual report every year.1

Following the recent release of his latest letter, we highlight a few of the messages we believe are good reminders for investors broadly.

“Paper money can see its value evaporate if fiscal folly prevails…Fixed-coupon bonds provide no protection against runaway currency…I have had to rely on equities throughout my life. In effect, I have depended on the success of American businesses, and I will continue to do so.”

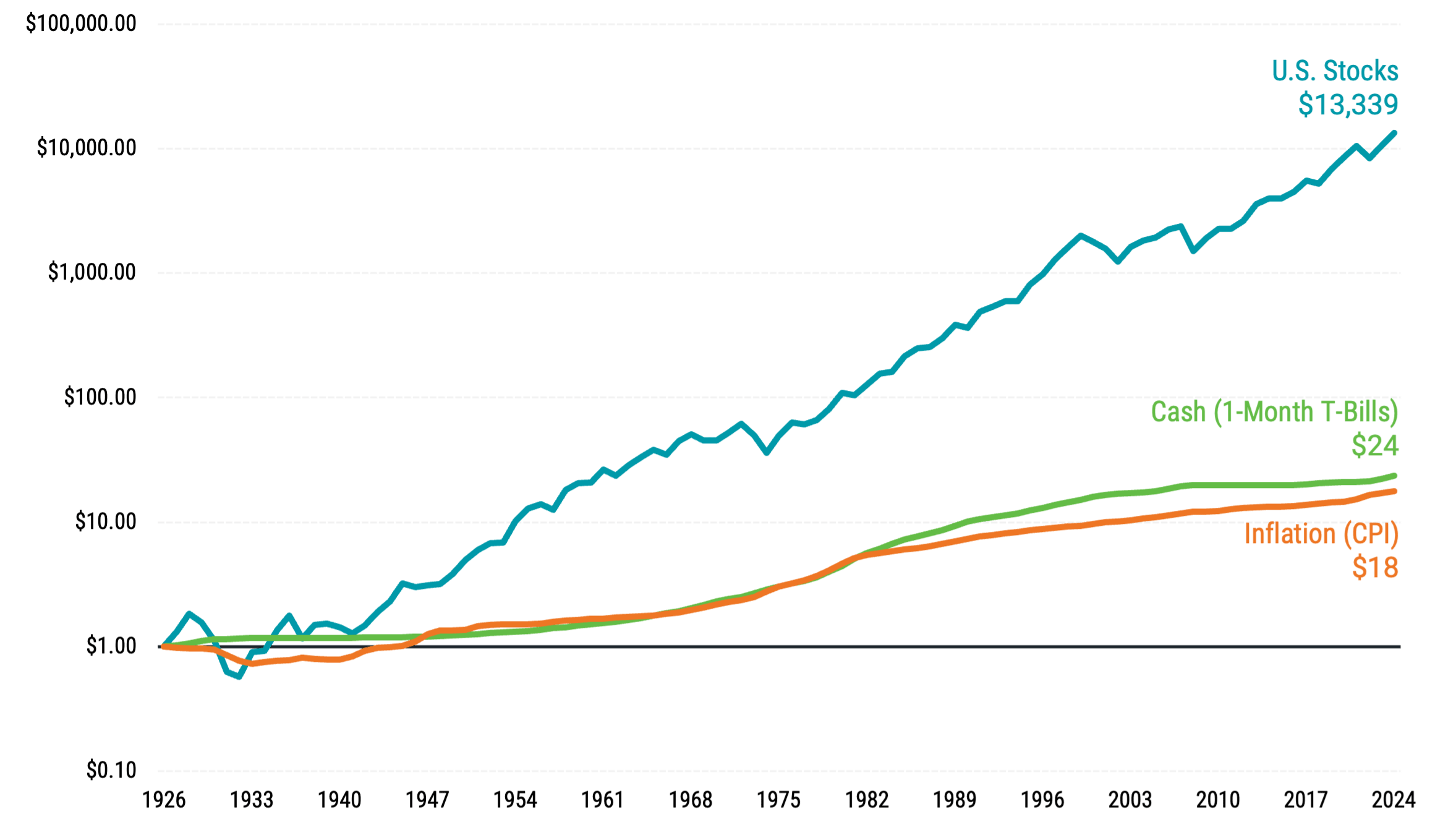

A consistent theme in the letter is a simple reminder of stocks' excellent track record in building long-term wealth even after inflation. Buffet points out that this important characteristic is unmatched by paper money or cash-like assets (e.g., short-term Treasuries or government money market funds).

It’s worth noting the highlighted messages appear in a section discussing Berkshire’s current cash position. This topic has received significant media attention, with some interpreting it as a sign that Buffett has grown pessimistic about the stock market. However, he sets the record straight that the vast majority of Berkshire’s assets remain invested in equities, and he intends to keep it that way.

We believe his words contain invaluable messages. They remind us that, as investors, there will always be reasons for anxiety. However, not investing in the market or leaving significant assets on the proverbial “sidelines” waiting for the perceived optimal time to invest introduces other risks. The potential deterioration of our savings' purchasing power is an important one.

Figure 1 shows why. We plot the growth of a dollar in U.S. stocks from 1926 through 2024 versus the growth of cash (based on the risk-free interest rate represented by one-month Treasury bills) and the rate of inflation, which captures price increases for goods and services over time. The results speak for themselves.

Figure 1 | Stocks Have Historically Provided a Far Greater Defense Against Inflation Than Cash

Growth of $1

Data from 12/31/1926 - 12/31/2024. Source: Ken French's Data Library. U.S. stocks are the market portfolio, and cash is one-month Treasury bills. Inflation is based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI), sourced from the Federal Reserve Bank.

The Power of Compounding Returns

Over nearly 100 years, cash beats inflation, but the gap pales in comparison to that of stocks and inflation. As Buffett often points out, the power of compounding equity returns over the long term is nothing short of magical.

“We simply looked at their financial records and were amazed at the low prices of their stocks.”

This single sentence from Buffet’s letter contains significant insights, as Buffett refers to a cohort of portfolio companies purchased in years past. After considering the strength of the underlying fundamentals, the prices of these companies were perceived to have good value. What’s made clear is that price matters and must be a consideration, but not in isolation.

Interestingly, if you’ve studied Buffett’s career, you know he hasn’t always held the same view of what makes an investment a good deal or “value.” His thinking has evolved from years of experience.

Evolving Investment Philosophy

As a student of Benjamin Graham in the 1950s, Buffett naturally followed Graham’s teachings early in his career. Some refer to Graham as the “godfather” of value investing. His strategy involved finding a company with a price so low that its total market value was lower than its net assets or book value (i.e., what it owns minus what it owes).

This didn’t mean or require that the company be viewed as a good or quality business. It just meant that, in theory, even if the company folded, its assets could be sold, and you should get back more than you paid.

Buffett often credits his long-time business partner and friend, Charlie Munger, with opening his eyes to an improved way of thinking. Munger pushed Buffett to seek “wonderful companies at fair prices” rather than average or lousy companies at wonderful prices.

Cheap companies often earn their low prices. Munger’s influence contributed to evaluating companies more holistically, not just looking at price and book value but also considering other relevant fundamentals like cash flows and profits.

These underlying concepts behind Buffett’s evolved thinking parallel the advancements in asset-pricing research over time. “Value” can be defined and measured in many ways. Still, historically, the most common form in asset-pricing models has been low company prices versus their book values with no consideration of cash flows or the company's quality.

Many strategies identified by name as value approaches, index-tracking and active strategies alike, still target companies in this way. But, similar to Buffett and Munger's thinking, the research shows that finding companies with both strong profits (sometimes referred to as high quality) and good prices (high book-to-market ratios) is an improved method for identifying value in an investment, as Figure 2 demonstrates.

Figure 2 | Value Is Found in Quality Companies with Good Prices, Not Just Low Prices

Panel A | U.S. Large-Cap Stocks, 1973 - 2024

Panel B | U.S. Small-Cap Stocks, 1973 - 2024

Data from 1973-2024. Source: Avantis Investors and Sunil Wahal, CRSP/Compustat, U.S. Securities. “Low Price Multiple” is defined as companies with a high book-to-market ratio. “High Profitability” is defined as companies with a high profits-to-book ratio and “Low Profitability” as a low profits-to-book ratio. Large-caps generally represent about the top 90% of the U.S. market capitalization while small-caps represent about the bottom 10%.

“Berkshire shareholders have participated in the American miracle by foregoing dividends, thereby electing to reinvest rather than consume. Originally, this reinvestment was tiny, almost meaningless, but over time, it mushroomed, reflecting the mixture of a sustained culture of savings, combined with the magic of long-term compounding.”

Did you know that Berkshire has paid only one dividend in the more than 60 years Buffett has led the company? Buffett even claims not to remember why he suggested the dividend to the Berkshire board in 1967, referring to it now as “like a bad dream.”

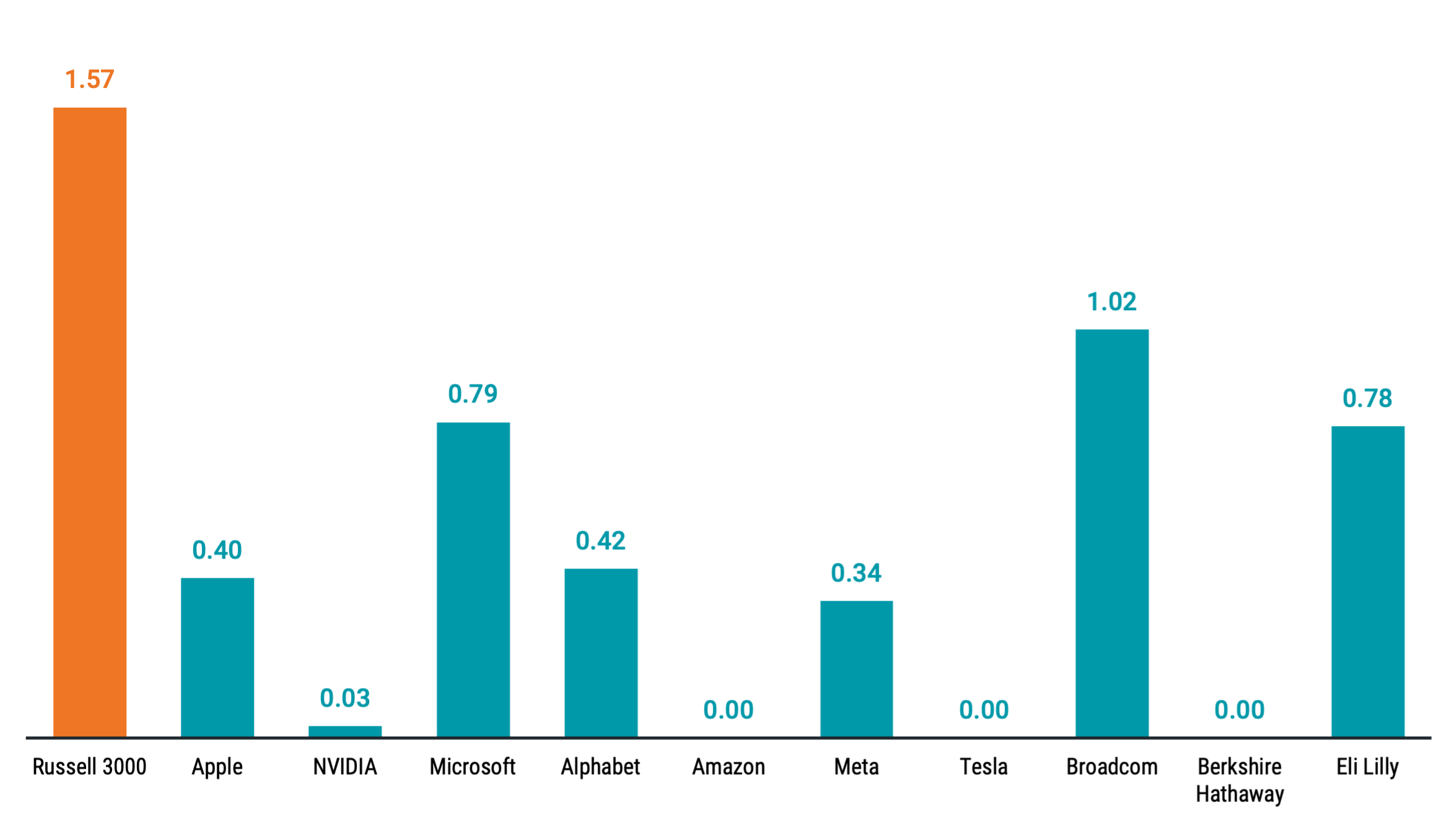

While many investors view dividends as an attractive characteristic, and many investment strategies are marketed for their high dividend yields, Buffett is pretty clear that he’d prefer to continually reinvest Berkshire’s cash rather than distribute it so shareholders may reap the benefits of compounding over time. Berkshire isn’t the only well-known, successful company that chooses not to pay dividends.

Figure 3 shows the top 10 largest companies in the U.S. market and their dividend yields at the end of 2024. Amazon and Tesla join Berkshire as non-payers, while we note that Alphabet and Meta paid their first-ever dividends in 2024. The absolute dollar amounts paid out by the payers among the top 10 aren’t small, but on a yield basis (dividend per share/price per share), all are well below the overall yield for all companies in the Russell 3000® Index.

Figure 3 | Several Top Companies Don’t Pay Dividends

Dividend Yield of the Top 10 Largest U.S. Companies as of December 31, 2024

Data as of 12/31/2024. Source: Bloomberg.

In our view, the relevant takeaway is that different companies make different decisions about dividend payouts. Dividends are, in fact, just that — a management decision. A company’s dividend yield in isolation can’t tell you the quality of the company or its total expected return. Companies may even pay dividends by borrowing instead of having good earnings.

As a result, an investment strategy seeking to maximize dividend yield may forego investment in non-dividend-paying companies with very attractive expected returns. If the goal is to understand something about expected returns, then it comes back again to looking at company prices and fundamentals more holistically.

Humility and Transparency Are Powerful Investment Traits

One final reminder that comes through in Buffett’s annual letters isn’t encapsulated by a single quote, though he speaks about it when referring to how often the terms “mistake” or “error” appear in his annual letters over the last few years (16 over the 2019-2023 period, to be exact).

Why does Buffett choose to be so transparent with shareholders? His language indicates that he sees it as his duty as CEO and expects Berkshire’s next CEO to follow suit. It’s also clear that he believes good investors should possess enough self-awareness to know they won’t get every decision right.

Buffett has amassed tremendous success and is forthright in acknowledging how many mistakes (in hindsight) he has made. Overconfidence bias has been studied extensively in the behavioral finance literature, and it can lead investors to make poor investment decisions as they overestimate their capabilities versus the market.

Buffett’s acknowledgment of the need to be honest with ourselves and others as we assess past decisions and contemplate new ones serves as a good reminder for investors. Have a plan. Try to focus on what you can control versus what you cannot. Stay the course.

Endnote

1 Berkshire Hathaway Inc., “2024 Annual Report,” February 22, 2025.

Glossary

Book-to-Market Ratio: Compares a company’s book value relative to its market capitalization. Book value is generally a firm’s reported assets minus its liabilities on its balance sheet. A firm's market capitalization is calculated by taking its share price and multiplying it by the number of shares it has outstanding.

Consumer Price Index (CPI): CPI is a U.S. government (Bureau of Labor Statistics) index derived from detailed consumer spending information. Headline CPI measures price changes in a market basket of consumer goods and services such as gas, food, clothing, and cars. Core CPI excludes food and energy prices, which tend to be volatile.

Dividend: A payment of a company's earnings to stockholders as a distribution of profits.

Dividend Yield: The return earned by a stock investor, calculated by dividing the amount of annual dividends per share by the current share price of the stock.

Expected Returns: Valuation theory shows that the expected return of a stock is a function of its current price, its book equity (assets minus liabilities) and expected future profits, and that the expected return of a bond is a function of its current yield and its expected capital appreciation (depreciation). We use information in current market prices and company financials to identify differences in expected returns among securities, seeking to overweight securities with higher expected returns based on this current market information. Actual returns may be different than expected returns, and there is no guarantee that the strategy will be successful.

Fundamentals: Factors used in determining value that are more economic (growth, interest rates, inflation, employment) and/or financial (income, expenses, assets, credit quality) in nature, as opposed to "technicals," which are based more on market price (into which fundamental factors are considered to have been "priced in"), trend, and volume factors (such as supply and demand), and momentum.

Market Capitalization: The market value of all the equity of a company's common and preferred shares. It is usually estimated by multiplying the stock price by the number of shares for each share class and summing the results.

Russell 3000® Index: Measures the performance of the largest 3,000 U.S. companies representing approximately 98% of the investable U.S. equity market.

U.S. Treasury securities: Debt securities issued by the U.S. Treasury and backed by the direct “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government. Treasury securities include bills (maturing in one year or less), notes (maturing in two to 10 years) and bonds (maturing in more than 10 years).

Yield: The rate of return for bonds and other fixed-income securities. Price and yield are inversely related: As the price of a bond goes up, its yield goes down, and vice versa.

Investment return and principal value of security investments will fluctuate. The value at the time of redemption may be more or less than the original cost. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.

The opinions expressed are those of the portfolio team and are no guarantee of the future performance of any Avantis fund.

References to specific securities are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended as recommendations to purchase or sell securities. Opinions and estimates offered constitute our judgment and, along with other portfolio data, are subject to change without notice.