Going Back to T+1

Key Takeaways

The move to T+1 settlement for U.S. securities represents a significant development expected to reduce counterparty risk for investors.

The shift is a continuation of a longer-term trend toward shorter settlement cycles driven by technological advancements.

Other non-U.S. markets have already enacted T+1, with more markets expected to follow suit.

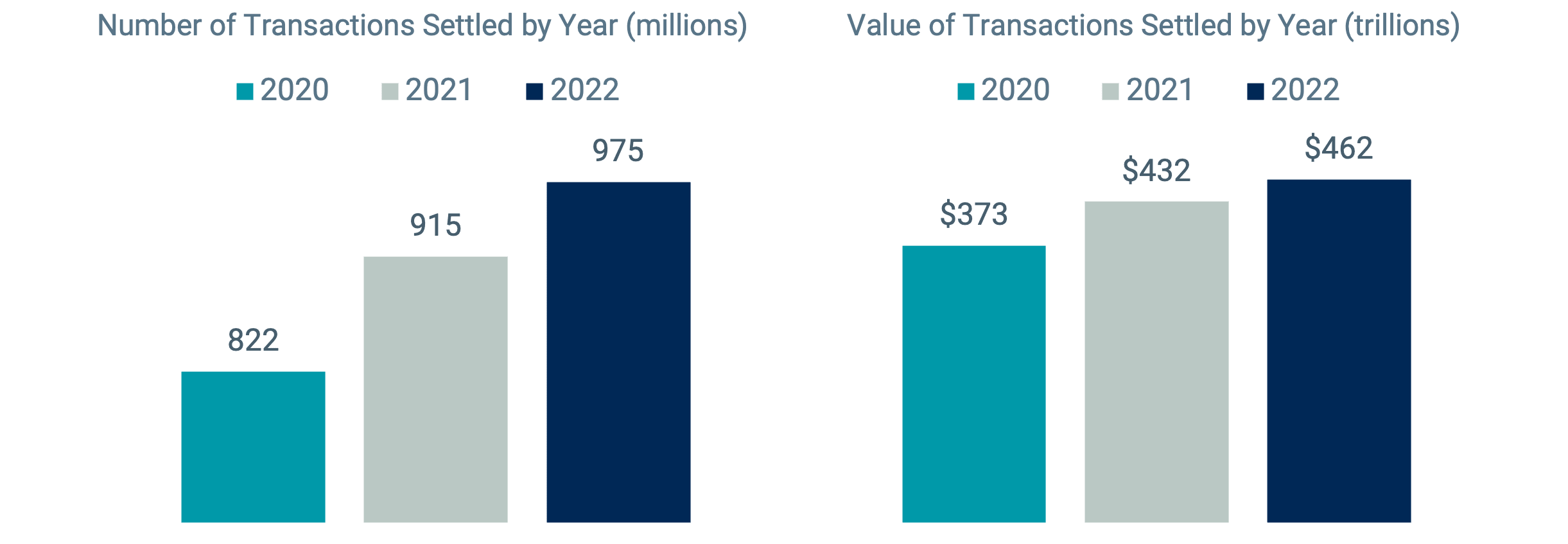

Every trading day, millions of U.S. security transactions are completed or “settled,” amounting to trillions of dollars in investor capital moving hands each year. Settlement marks the final step in a trade's lifecycle. It's when the buyer fulfills their payment obligation, and the seller delivers the promised securities.

Despite the massive scale of daily security transactions and the incredible effort of our financial system to support reliable settlement processes, few investors are likely to give it much thought. The transfer of cash and securities between investors typically happens electronically behind the scenes. Yet, recently, the inner workings of the settlement cycle have been cast into the limelight of popular discussion.

Figure 1 | Millions of Transactions Worth Trillions of Dollars Settle Each Year

Data as of 12/31/2022. Source: Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation.

The Move to T+1 Settlement Cycle

The reason is that on May 28, the settlement cycle for U.S. securities, such as stocks, bonds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), adopted a new standard requiring settlement to occur one business day after a transaction takes place. This is widely referred to as the move to “T+1” (i.e., settlement date one day after transaction date) from the previous “T+2” standard (i.e., settlement date two days after transaction date).

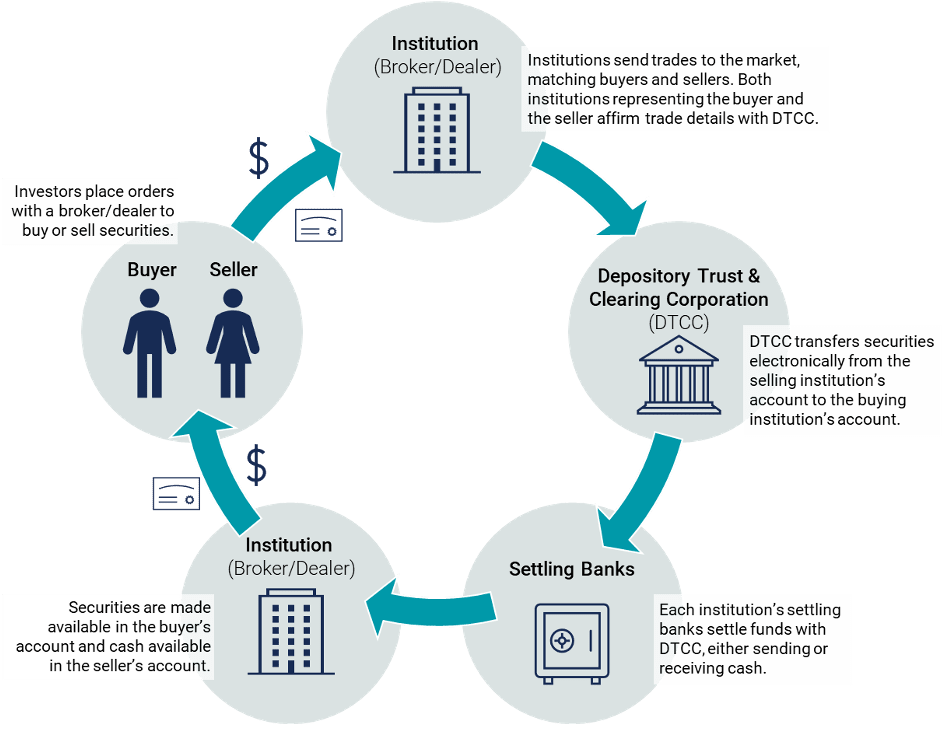

To uncover why this matters for investors, we start with a basic overview of the trade lifecycle as shown in Figure 2. When initiating a trade, today’s investor typically submits an order with a broker/dealer to buy or sell a security. A confirmation usually soon follows that the order has been filled. However, this doesn’t mean the trade has settled and that cash is now available in the seller's account and new securities are now available in the buyer's account.

Figure 2 | Lifecycle of a Trade

Source: Avantis Investors, Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC). Certain activities attributed to DTCC are, in practice, performed by subsidiary entities that handle clearing and transfer processes.

Steps Involved in the Securities Settlement Process

To carry the trade through to settlement, multiple parties get involved. This often includes an institution representing the buyer and another representing the seller (e.g., the broker/dealer through which the trade was initiated) and the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. (DTCC) and its subsidiaries that handle clearing and transfer activities — the National Securities Clearing Corp. (NSCC) and the Depository Trust Co. (DTC). Importantly, the DTCC serves to reduce risk in the financial system, acting as a neutral intermediary that helps enforce and facilitate the responsibilities of the buyer and seller and insure investors against the risk of default by the buyer, seller or institutional counterparties involved in the trade.

Each institution is required to affirm the details of a trade with DTCC, which then electronically transfers ownership of securities between the institutions and oversees the transfer of funds with the institution’s settling banks. It all concludes with cash and securities being made available in the trading investors’ accounts.

Benefits of Faster Settlement

What benefit is there for investors by shortening the time to complete this full process? The upside is in reduced counterparty risk.

Imagine you make a friendly wager with a friend, and you agree that the loser will owe the winner a certain amount of money two days later. Over the course of those two days, the loser realizes that after an unexpected expense, they don’t have the money to make the winner whole. Had you agreed to payment one day later rather than two, the risk of something unexpected causing the deal to fail would be lower.

This same logic applies to security settlement. The longer it takes a trade to settle, the greater the chance that the buyer, seller, or the institutions they are working with will be unable to fulfill their obligations.

While reduced counterparty risk is a key benefit of the move to T+1, there are a few other considerations worth noting:

First, another motivation for faster settlement was born out of events from the 2021 “meme stock” craze. DTCC issues margin calls to brokers to maintain sufficient funds to insure investors against counterparty failure. In times of higher volatility, margin requirements typically increase. This was the case for brokers like Robinhood, with significant exposure to meme stock trades. Unable to meet the margin calls, it halted further trading in those names, angering some investors but helping to reduce their money owed to DTCC. Shorter settlement can also reduce the required margin by lessening the risk of trade failures and, in turn, potentially reduce the likelihood that brokers will need to institute trade restrictions.1

Second, for fund investors, the move to T+1 also means that ETFs and mutual funds now settle on the same timeline. This alignment may help alleviate previous rebalancing issues for investors who allocate across ETFs and mutual funds.

You might also ask how it can be expected that all the steps of a trade can be completed for millions of transactions within a single day. First, consider that most U.S. security transactions today occur electronically. Gone are the days when investors had to deliver physical certificates of ownership to complete a trade. As technology and the speed of information processing have improved, so too has the ability to more efficiently and quickly settle trades.

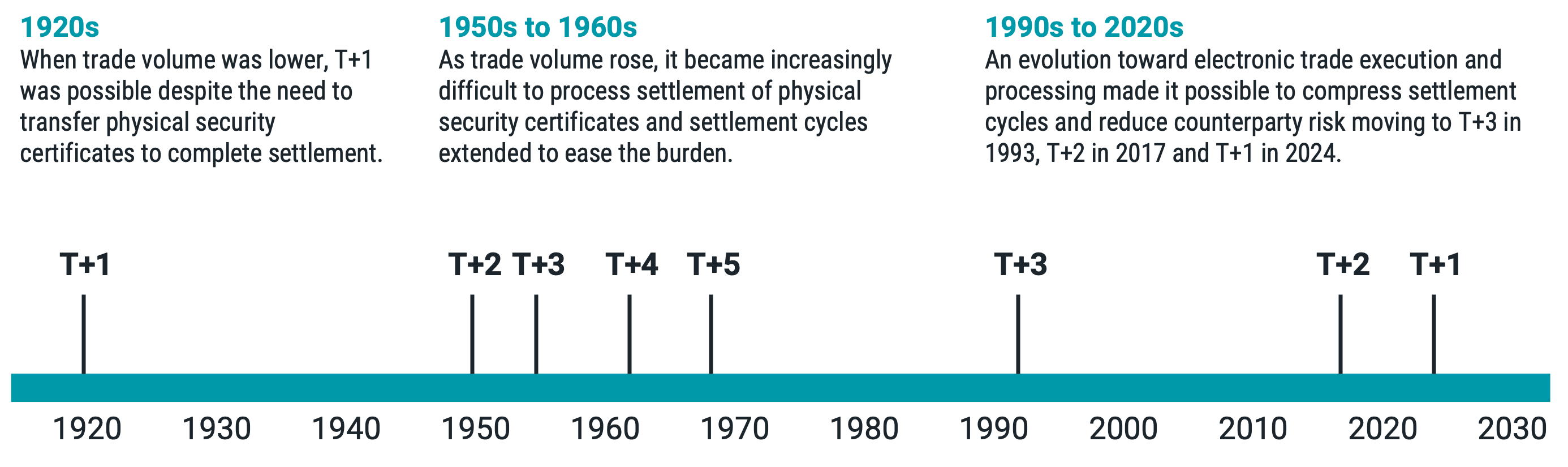

In Figure 3, we show a historical timeline of changes to the settlement cycle in the U.S. It’s interesting to note that most securities settled T+1 looking back 100 years. As time went on and trading volume rose, settling trades with physical security certificates became difficult to manage, and the settlement cycle gradually extended.

Figure 3 | The Recent Move to T+1 Continues an Ongoing Effort to Settle Trades Faster for U.S. Investors

Source: Avantis Investors.

The more important point is that in the past few decades, as technology has advanced and electronic processing has become the norm, we’ve seen a compression of the settlement cycle. The recent shift back to T+1 can be viewed as simply a continuation of a longer-term effort to complete trades faster and reduce risk to investors. And this might not be the end of the trend. We may eventually reach T+0, which some across the industry, including regulators, are already discussing.

The International Shift to Faster Settlement Cycles

The U.S. isn’t the first country to adopt T+1. India implemented the shorter settlement cycle last year, while Canada, Mexico and Argentina moved to T+1 in late May just before the U.S.

Chile, Colombia and Peru plan to do the same in 2025. The EU and UK are also exploring T+1, with implementation possible in the coming years. It’s clear that there is increasing global alignment on the merits of faster settlement and that it’s been achieved elsewhere can offer some comfort it can also be done in the U.S. without a meaningful impact on investor experience.

Finally, while it’s still early days since the official transition from T+2 to T+1, signs so far have been positive as to the industry’s preparedness to deliver. For example, while some predicted a meaningful increase in trade failure rates because of the change, failures have remained low under T+1. This has, in part, been aided by same-day trade affirmations from brokers/dealers coming in at a higher-than-expected clip.

Remember that affirmation is required before DTCC initiates security and cash transfers. Before T+1 implementation, DTCC set a target of 90% for same-day affirmations, and as of May 31, the actual rate was near 95% — a good sign that a well-functioning market can be maintained under T+1.2

So, what’s the bottom line? Reducing the U.S. settlement cycle surely comes with complexity given the incredible volume of daily transactions. However, we believe the benefit of reduced risk to investors makes it a worthwhile endeavor.

1 Source: Wall Street Journal.

2 Source: Yahoo! Finance.

Glossary

Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF): An ETF represents a basket of securities that trades on an exchange, similar to a stock. An ETF differs from a mutual fund in that its share price fluctuates all day as investors buy and sell the ETF. A mutual fund’s net asset value (NAV) is calculated once per day after the market closes.

Investment return and principal value of security investments will fluctuate. The value at the time of redemption may be more or less than the original cost. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.

The opinions expressed are those of the portfolio team and are no guarantee of the future performance of any Avantis fund.