Coronaviruses, Pandemics and the World Economy

The coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak continues to make headlines, and stock markets worldwide have felt the influence of the uncertainty it has brought. While the World Health Organization hasn’t yet classified this latest infectious disease outbreak a pandemic, it’s worth looking at past pandemics to evaluate their effects on the world economy and stock markets. The nature of widely spread outbreaks makes it difficult to determine precise beginning and end dates for each event—even in hindsight—but we have historical data to guide our analysis.

Much has been published about pandemic influenza. Ten events have occurred over the last 300 years, including three in the 20th century.1 Of those in recent history, the 1918 pandemic (Spanish flu) had the most significant impact, infecting some 500 million people worldwide and killing 40-50 million—surpassing the combined civilian and military casualties of World War I.

We have also seen viruses that presented immediate threats and caused severe anxiety but whose effects were somewhat limited. An epidemic of SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus spread worldwide from Asia in 2003.2 MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome, another coronavirus) was first detected in September 2012 in Saudi Arabia. Previous cases of MERS back to April 2012 were later identified in Jordan.3 The 2009 swine flu spread worldwide, infecting around 60 million people in the United States before the outbreak ended in August 2010.4

Effects Are Hard to Predict

In 1918, the measures available to mitigate a pandemic were limited and primarily non-pharmaceutical. Since that time, we’ve seen vast improvements in medical care and diagnostic techniques, the development of antiviral drugs and vaccines, and extensive emergency preparedness planning based on research and lessons learned.5 Advances in biotechnology, for example, allowed researchers in China to quickly identify the DNA structure of COVID-19 only a month after the virus first appeared in December 2019. New tests to rapidly detect COVID-19 and identify infected individuals are already in testing, and potential vaccines are in development and expected to go into trials soon.6

In 2005, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) prepared an assessment that attempted to estimate the effects of a pandemic on the U.S. economy.7 The EU and other countries conducted comparable assessments.8 The CBO found that a “1918-style pandemic,” where as many as 30% of workers in each sector became ill, could have an economic impact like an average post-World War II recession. A milder pandemic, like those of 1957 and 1968, would cause a slowdown in gross domestic product (GDP) growth but “might not even be distinguishable from the normal ups and downs of economic activity.”

Based on what happened in Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak, the CBO estimated the stock market would fall initially and then rebound. A Canadian study cited in the EU’s economic report noted immediate contraction in quarterly economic growth in Hong Kong surrounding SARS, but a subsequent spike in growth the following quarter, indicating delayed consumption.9 This pattern was also identified surrounding Spanish flu, with studies noting that November-December 1918 retail sales fell by about 2% and 6%, but January 1919 sales growth jumped by about 8%.

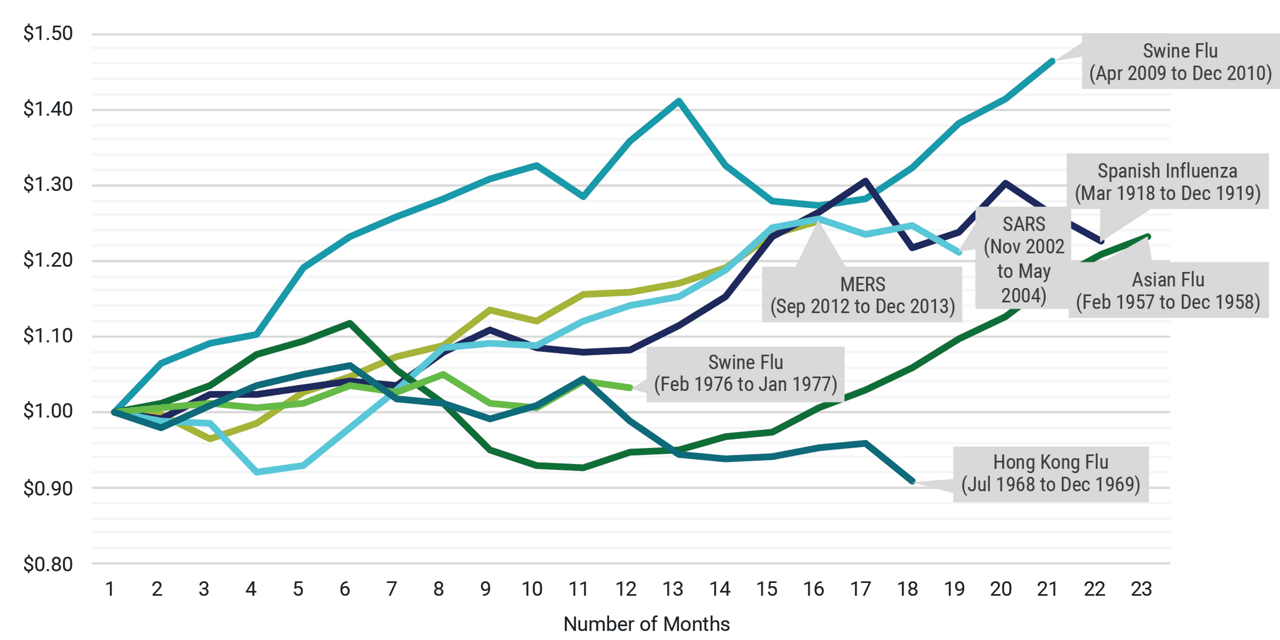

But what about stock markets? In Figure 1, we plot the growth of $1 for the S&P 500® Composite Index in the months following the first reported cases of several outbreaks throughout history and show the ending value when the outbreak subsided. As previously mentioned, there is much uncertainty associated in determining the measurement periods and precise length of each outbreak. It’s impossible to disentangle the market effects of the outbreak itself from other economic forces. The sell-off across stock markets in recent days was attributed to fears surrounding the impact of the coronavirus but happens to coincide with valuation ratios on the high side relative to historical averages for equities.

FIGURE 1 | GROWTH OF $1 DURING OUTBREAKS

Sources: Robert Shiller Data Collection at Yale University and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. S&P 500® Composite Index does not include reinvested dividends.

Regardless of its classification as an epidemic, pandemic or otherwise, an outbreak’s effects are hard to predict. Different entities worldwide have analyzed the impacts of historical outbreaks to assess the potential effects of a new pandemic considering ongoing scientific and technological breakthroughs. For example, the timeline for vaccine development (as measured by the genetic-sequence selection to the first human study) is projected to be about three months for the virus associated with COVID-19. This is astonishingly fast compared to vaccine development for the 2003 SARS coronavirus, which took 20 months.

For investors wondering about the impact of such events on their portfolios, there are no certain answers. Potential negative impacts on certain industries range from travel restrictions and decreases in manufacturing productivity to positive effects on others such as increased demand for medical supplies and vaccines. What will matter most is how these outcomes compare to the expectations already embedded into prices from market participants. Like the historical outbreaks we’ve discussed, determining the precise impact of coronavirus on the global economy and stock markets, even after the fact, will be challenging. If history serves as any guide, however, panic is unlikely to be the best response. Increased uncertainty frequently brings increased volatility, so in these times thoughtful asset allocations within the context of long-term financial plans are as important as ever.

ENDNOTES

1 Potter, C.W. 2001. “A history of influenza.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 91, no. 4 (October): 572-579. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). https://www.cdc.gov/sars/index.html

3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). https://www.cdc.gov/mers/about/

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009 H1N1 Pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus). https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/2009-h1n1-pandemic.html

5 Jester, Barbara, Timothy M. Ukeki, Anita Patel, Lisa Koonin, and Daniel Jernigan. 2018. “100 Years of Medical Countermeasures and Pandemic Influenza Preparedness.” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 11 (November): 1469-1472. https://dx.doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2018.304586

6 Bai, Nina. 2020. “How the New Coronavirus Spreads and Progresses—And Why One Test May Not Be Enough.” University of California San Francisco News, Feb. 13, 2020. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2020/02/416671/how-new-coronavirus-spreads-and-progresses-and-why-one-test-may-not-be-enough

7 Congressional Budget Office. 2005. “A Potential Influenza Pandemic: Probable Macroeconomic Effects and Policy Issues." December 8, 2005. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/109th-congress-2005-2006/reports/12-08-birdflu.pdf

8 Jonung, Lars and Werner Roeger. 2006. “The macroeconomic effects of a pandemic in Europe—A model-based assessment.” European Economy Economic Papers 251, (June). Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication708_en.pdf

9 James, Steven and Tim Sargent. 2006. “The Economic Impact of an Influenza Pandemic.” Working Paper 2007-04. Department of Finance Canada. December 12. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2008/fin/F21-8-2007-4E.pdf

GLOSSARY

Gross domestic product (GDP). GDP is a measure of the total economic output in goods and services for an economy.

S&P 500® Composite Index. This index of 500 widely held common stocks measures the general performance of the market.

The opinions expressed are those of the investment portfolio team and are no guarantee of the future performance of any Avantis Investors portfolio.

This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.

This information does not represent a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a security. The trading techniques offered do not guarantee best execution or pricing.

The contents of this Avantis Investors presentation are protected by applicable copyright and trade laws. No permission is granted to copy, redistribute, modify, post or frame any text, graphics, images, trademarks, designs or logos.